A Case Study on Filipino Martial Arts

Manolo Luis C. del Rosario

Introduction

Mindanao island is marked by diversity. It is home to three distinct groups who compose the majority of the population. These are the Christianized groups, the Muslim tribes and the indigenous Lumad tribes scattered throughout the island. The Christianized group is comprised of indigent Lumads who have been converted to Christianity as well as migrant settlers from other parts of the country. We have Ilonggos, Ilocanos, Boholanos and Cebuanos, each with their distinct ethnic idiosyncrasies. Then there is a significant Filipino-Chinese community as well who, likewise, have their own sets of cultural norms.

Given this context of a non-homogenized population living in close proximity to each other, the need for balance and harmony comes to the forefront. Our collective relational imperatives play a major role in preserving and encouraging this harmony and balance. For those who live in Mindanao, this kind of sensitivity to cultural norms becomes so ingrained, it expresses itself in everyday life on an unconscious level. For us Mindanaoans, for example, it has become natural to always consider the dietary restrictions of others based on their religious beliefs. In social gatherings, care is taken to consider the guest list and see to it that the activities and food served are appropriate. When invited by the Filipino-Chinese community, we take extra care to ensure that what is worn is appropriate. You never wear white for a joyous occasion for example as this is often associated with mourning when it comes to Chinese culture.

The Davao Experience: A Reflection

Davao is home to a population of more than two million people. It is considered the socio-economic hub of Mindanao. As such, it is a convergence point for people from across the island and across the country. It is home to a very diverse population base representing all three major people categories present on the island (and all its sub-categories) – the Christianized groups, the Muslims, and the indigenous Lumad tribes. It is a melting pot of culture, which gives it very unique opportunities and very unique challenges as well. Many of these challenges deal with maintaining balance and harmony in such a diverse context.

Faced with such challenges, one would think the best recourse is to homogenize the population by suppressing distinct ethnic identities. This is, however, not the route Davao takes. Instead of seeing this diversity as a source of problems, Davao City celebrates its diversity on every occasion. Festivals such as the Kadayawan are excellent examples of this. During city-wide festivals such as the Kadayawan and Araw ng Dabaw, all tribes are represented in the various events throughout the city. Unique ethnic identities are brought into the spotlight.

In Davao, community activities are designed to be non-partisan and ecumenical, taking into consideration the various belief systems present in the community. Active participation by all stakeholders is encouraged. There is always room for ethnic identity. In recent years, this has even included accommodation of the Hindu Duwali Festival in recognition of Davao’s sizeable Indian population! Davaoeños do not see their differences as hindrances to social development. On the contrary, we celebrate the differences and corresponding diversity this brings to the table while emphasizing the commonalities we have as Mindanaoans and as Davaoeños – the shared dreams and aspirations we have as a people.

We emphasize “kapwa.” As such, extra steps are taken to bring people together in the hope that through relationships and interaction, cross-cultural misconceptions and biases are demolished. By celebrating our diversity while emphasizing our similarities, while relying on various relational imperatives inherent in all of us, Davaoeños hope to strengthen social harmony and unity without losing our individual tribal, ethnic or religious identities – a unity within the context of diversity. It may not be perfect, and challenges related to multi-diversity remain. But with the conscious and consistent effort at multi-sectoral dialogue and interaction, these challenges are addressed little by little.

In times of natural calamities, Davaoeños spring into action. The city is known for its fast and collective social response in providing aid to our calamity-stricken countrymen. Relief collection activities are organized across the socio-economic spectrum. We see individuals who have meager resources to share go to relief centers and donating a single kilo of rice out of the desire to help. As an avid mountaineer, it is but normal for this author to ask his tribal guides whether they eat pork or not prior to having a meal or educate himself on the proper etiquette while in the mountains, taking tribal beliefs into consideration. These are all expressions of Filipino relational imperatives such as delikadesa, awa, pakikiramay and pakikitungo towards our kapwa Davaoeño, kapwa Mindanaoan, and kapwa Filipino.

This writer’s Davao-based Filipino Martial Arts group likewise serves as a microcosm of Davao. These Filipino cultural norms are expressed not just in group dynamics and interpersonal relationships, but within the very structure and physical practice of the art itself. It is through expressions in physical practice, conceptual paradigm and teaching methodology that these relational imperatives are ingrained, both consciously and unconsciously. Thus we have a collective which, despite its diversity in membership (a diversity which crosses religious and socioeconomic lines), is united and connected by a common love and shared goal. Within the context of our FMA group, Filipino relational imperatives, values and worldview create a unifying factor which ensures group solidarity, balance and harmony.

It is not just Davao which has overtly demonstrated these relational imperatives. In a display of awa, pakikiramay and utang-na-loob, Taclobanons strongly expressed their collective support when Davao was hit with a terrorist bombing. This was no doubt because they did not forget how Davao was there for them in their time of greatest need, when Typhoon Yolanda struck. These examples show how the concept of kapwa, ingrained in one’s kalooban and supported by our cultural imperatives, fuels social collective action. It shows how an awareness that we are all in this together; that we are “one” expresses itself in the greater Filipino society.

All these overt expressions of Filipino relational imperatives are inherent in all of us regardless of tribe, religious or socio-economic background. These imperatives did not develop in a vacuum, however. These were preserved and encapsulated within every facet of Filipino life; in language, education, dance, oral traditions, music. Filipino cultural elements reflect our value system, and this is true even for something as seemingly unrelated as martial arts.

The Filipino Martial Arts (FMA) refers to a group of traditional Filipino martial art traditions specifically referring to the arts known also as Arnis, Escrima, or in more recent times, Kali. These are weapon-based martial art systems which encompass the use of various weaponry (bladed, blunt, long, short) as well as empty hand techniques that are generally focused on defenses and counters against weaponry. It is not a single art but rather a collection of similar martial traditions which sprung from different parts of the Philippines. While it is generally lumped under the aforementioned terms, it is actually composed of different systems with different evolutionary tracks. Some systems may share similar influences, some may have common roots, and most may share the same principles and methodology. Despite this, however, these systems are nonetheless considered to be distinct from one another with identities of their own.

Through this chapter, this author hopes to show how deeply ingrained these cultural norms and values are within the practice of Filipino Martial Arts and provide a glimpse of the potential and value cultural elements such as these have in helping forge a harmonious and socially inclusive society.

History

There are several theories on the origins of the Filipino Martial Arts and they continue to be a hot topic of debate among practitioners and researchers today. The oldest theory of origin suggests that these arts predate the arrival of the Spanish in 1521. First suggested by Placido Yambao and Buenventura Mirafuente in the book Mga Karunungan sa Larong Arnis (University of the Philippines Press, 1957), this theory was likewise suggested by later authors such as Dan Inosanto in his book Filipino Martial Arts (Know Now Publishing Company, 1980)and Dionisio Canete in Eskrima Kali Arnis (Doce Pares Publishing House, 1993). While these authors based this history on oral tradition, non-existent archaeological and written evidence has put these theories into question (Nepangue 2001, 9-14; Jocano 2001, 3-8).

A more recent theory on the origins of these arts suggests that FMA as we know it today is the product of the Spanish occupation of the Philippines. This theory was proposed by Celestino Macachor and Dr. Ned Nepangue in the book, Cebuano Eskrima: Beyond the Myth (XLibris, 2007). They argue that while there is no evidence of a pre-colonial organized martial art akin to FMA as we know it today, there is, however, evidence of our ancestors learning the rudiments of European Fencing from our Spanish colonizers. This transfer of fighting technology was borne out of necessity as Christianized villages needed to defend themselves against the Moro raids which were prevalent during that era (Macachor/Nepangue 2007, 65-78). Concurrent to this, our early ancestors also engaged in insurrections against the Spanish themselves, thus unwittingly taking lessons on fighting from their own enemies (Wiley 1996, 47-57). This knowledge was likely merged with the rudimentary fighting skills of the Filipino natives into what we know today as Arnis, Escrima or Kali. This is the more widely accepted theory on FMA origins today.

This acceptance is due to several reasons which include the accepted fact that while there are indeed certain similarities between FMA and European swordplay there are major differences in application, teaching principles and methodology, the acknowledgement that certain specific techniques exist in FMA which do not have similarities or counterparts in European swordplay, and the recognition that since Pre-Hispanic times, Filipino warfare was characterized by the use of various weaponry – bladed, blunt, long, short, projectile (Scott 1994, 147-150; Wiley 1996, 116-131). Due to this, it would then be reasonable to assume that they indeed had a body of knowledge on the use of these various weaponry whose practice may not be in a manner we recognize today as FMA, which was then fused with the added knowledge gained from the Spanish colonizers, either as friends or as enemies (Inosanto 1980, 11).

Over the centuries, other martial arts traditions have left their mark and influence on the Filipino Martials Arts as well. As a multi-cultural archipelago which has had contact with the Japanese and Chinese, and with the presence of the Muslims in the south (who have their own martial arts traditions of Silat and Kuntaw [Kuntaw itself being a mix between Indo-Malayan Silat and Chinese Kung Fu]), these influences are inevitable.

FMA (arnis/eskrima/kali) history traces itself predominantly from the central and northern parts of the Philippines. These include the Visayas and the Tagalog regions all the way to the Kapampangan areas. Through the migration of populations, some of which included practitioners, these arts spread all over the entire country from the northern tip of Luzon to Southern Mindanao. Because of this, FMA can be said to be a truly “national” martial arts heritage.

Regardless of the actual roots of FMA in Philippine history, it is evident that this art exists and has existed for at least 200 years and that it is unique to Philippine culture in its training principles and methodologies. As such, it is a priceless heritage which reflects elements of the Filipino Worldview and Value System in its training methodology, presentation of material, social structure, and sub-culture.

Physical practice: Teaching Principles and Methodology

Modern FMA practice is relatively undeveloped when compared to other martial arts traditions of countries such as Japan, Korea and China in terms of overall organizational structure (Wiley 1996, 341-344). Despite this, the teaching principles and methodology of traditional FMA practice reflect a highly sophisticated understanding of both the learning process and the realities of hand-to-hand weapons-based combat.

The teaching principles and methodology were products of necessity as early practitioners were considered “ordinary people.” These were village folk; farmers and fishermen who had other responsibilities such as planting and harvesting, fishing and hunting, providing for the general needs of their families and communities (Macachor 2007, 70-71). As such, they did not have the luxury of time to train. Yet, these same individuals were tasked with the defense of their communities when needed. It is in this context that early teachers were forced to devise ways and means by which to efficiently impart FMA knowledge and ensure an accelerated learning curve. This was achieved by distilling key concepts of teaching and application within the context of their very own culture.

Scope of training

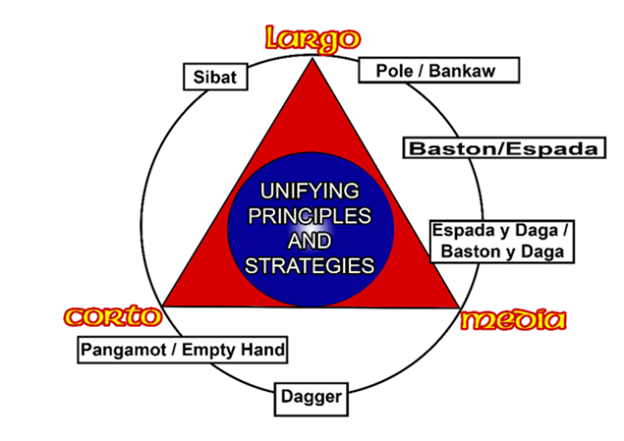

The scope of FMA is extensive. It involves the use of various types of weaponry each with its inherent characteristics. These include long bladed weaponry such as bolos, spears and swords, long blunt weaponry such as sticks of various lengths, and short weaponry such as daggers. Added to this plethora of weaponry are various empty-handed techniques meant to counter attack from such weaponry. FMA practitioners also routinely mixed these weapons in combinations and example of which is the “Espada y daga” (sword and dagger). A complete scope of FMA includes single and double sticks, single and double swords/bolos, single and double daggers, stick/sword and dagger (baston/espada y daga), short/pocket stick also known as “dos pontas,” two-handed long stick known as “dos manos,” long pole/spear, and empty handed techniques generically called “Suntukan” or “Pangamot” which includes use of the hands to hit (suntukan), kicking (sikaran), joint manipulation, locking and breaking (trancada) and rudimentary grappling (buno/dumog).

It is important to note that while this scope reflects the potential variety of components in FMA, not all FMA systems/schools practice this wide variety of components. Some FMA systems choose to specialize in specific formats. Systems such as Balintawak Arnis prefer to focus on single stick and empty hand techniques, while others such as Baraw Sugbu and Sayoc Kali prefer to specialize in the use of the dagger. In addition to this, other more exotic formats are also practiced by a few FMA systems. These include the use of flexible weapons such as handkerchiefs/scarves and whips, and even projectile weapons such as blowguns and bows/arrows. Most FMA systems however do contain at least the first four formats (sticks, bolos, daggers, espada y daga). This is a practical choice as these are objects commonly found in a typical Filipino rural household and therefore the easiest to use due to accessibility. Even in these modern times, one will often notice bolos hanging from the sides of farmers as they tend to their fields.

Philosophy of teaching: The principle of inter-relation

Given the extensive scope FMA covers, one is led to ask: How can such an extensive art be imparted? This is where the genius of FMA teaching methodology comes into the picture. These various formats are unified by underlying core principles. These principles may be in the form of specific techniques, combat strategies, or a combination of both. Through these core principles, the various components are unified. While other martial arts tend to adopt a technique-based approach, FMA follows a principle-based approach. Through this, a solid base of readily applicable responses is created since the techniques and strategies can apply to varying situations. Without a thorough understanding of underlying principles, martial arts practitioners will be hard-pressed when faced with situations they were never exposed to.

Figure 1. Image by the author.

This teaching approach starts from day one. On their first session, students are taught what is generally termed the “Abecedario.” This is akin to learning letters before learning to read. This is usually in the form of numbered strikes with specific angles and anatomical targets using a stick. While this can start specific, over the course of instruction, the student will come to learn that these angles of attack are 1) Applicable to different types of weapons (bladed, blunt, long, short); 2) Applicable to different targets depending on the level from which it was launched making a diagonal downward hack applicable to target the head, torso or even lower extremities. Thus, a practitioner who learns the first two angles and all its permutations both offensively and defensively, is theoretically equipped to apply or respond to any attack regardless of target, granting they fall into the same two angles. The same is true with regard to the weapons used. An angle one strike with a stick is basically the same angle with a dagger. The late Master Johnny Lacoste was once quoted as saying, “I tell you true, you learn the first two numbers, you can fight any style and beat him” (Inosanto 1980, 28).

FMA practitioners learn to adapt to similar situations regardless of the variable factors. This methodology gives FMA practitioners a high level of adaptability seldom seen among practitioners of other martial arts traditions. They can pick up an object, asses its inherent characteristics, and put it to use. By simplifying the otherwise wide scope of FMA, unifying these through a common principle-based center, practitioners are then able to learn and even create something new by relating it to something familiar. As a matter fact, many traditional FMA teachers jump between lessons, often giving snapshots of more advanced techniques and applications to ensure thorough understanding. The core principles of a system are presented using different perspectives similar to seeing the different sides and corresponding nuances of a sculpture from different angles.

1a-Baston (Stick)

1b-Baston (Stick)

2a-Espada (Sword)

2b-Espada (Sword)

3a-Daga (Dagger)

3b-Daga (Dagger)

4a-Pangamot (Empty Hand)

4b-Pangamot (Empty Hand)

Skills development: Interactive approach

Skills development in FMA is another area of differentiation when compared to other martial arts traditions. The main avenue by which practitioners develop fighting skills is through the extensive use of interactive partner drills. Through these drills, specific aspects such as footwork, body positioning, timing and striking accuracy are developed. Through these drills, proper responses become instinctive. There are practically hundreds of interactive partner drills in FMA, each system usually having its own set of drills based on the system strategies, range preference, or perceived developmental needs of the student. These can however be characterized into three types:

- Sequence/Choreographed Drills based on the memorization of a pre-determined sequence of strikes and responses between drilling partners.

- Semi-freestyle Drills whereby the feeding may be random, but the responses are set/specific.

- Freestyle Drills where all strikes and responses are random. Next to actual sparring, freestyle drills are the closest that practitioners will get to an actual fight. In these drills, practitioners rely purely on instinctive responses.

It is through these drills that practitioners learn by doing. It is argued that this heavy reliance on interactive drills is what makes FMA distinct from other martial arts traditions with the exception of the grappling arts which rely heavily on sparring for skills development. FMA training is a one-on-one affair which relies on relations and intimacy. While this can be said to be one of its greatest strengths, it is also its greatest weakness as it makes teaching the art on a mass basis next to impossible.

FMA teachers need to regularly interact with their students on a one-on-one basis if knowledge is to be properly passed on and skills properly developed. This need naturally puts a cap on the number of students an FMA teacher can effectively teach. In all cases however, senior students help in this regard. They guide the newer practitioners in their lessons and are tasked with leading them in partner drills. The learning process in this context is two-way, in that senior students learn by leading while newer students learn by responding. In this atmosphere, students develop an appreciation for others in helping them develop themselves, and the need for community if one is to become good at what he or she does. This breeds a co-dependency and strengthens ties within their FMA community. FMA practitioners know that if they are to achieve their goals as martial artists, they cannot do it alone.

As a people, Filipinos are relationists and not individualists. We want to be part of a group. The negative cultural connotation we relate to “kanya-kanya” (to each his own) shows how we view individuals who do not share this cultural norm. The modern emphasis on individualism is not part of traditional Filipino culture but is rather the product of a western education system (Jocano 1997, 63). This Filipino relationist cultural trait is expressed and even reinforced through the methodology devised by early teachers of FMA and given life through the various drills used by the countless FMA systems.

Concept of Time and Space

The Filipino concept of time and space reflects our worldview as well. While cognizant of the forward/linear movement of time in that it never regresses, Filipinos still see time as a cyclical continuum or what anthropologist Edward Hall calls “polychronic time.” As such, time is reckoned in terms of cycles defining the sequence, logic, and meaning of events. In this perspective, time is something to be enjoyed (Jocano 1999, 45). Events such as social gatherings, for example, while existentially having definitive beginnings and endings, flow from one to the next where succeeding events are reckoned as continuations of previous ones.

Time and space in traditional FMA practice holds existential value. It is dictated by the presence of the master/instructor. As such, learning is not confined to the four walls of a school nor to the defined schedule for training. Learning can happen anywhere, at any time (Wiley 1996, 87-88). Practice sessions are seen as part of a cyclical continuum which never really ends. A great many FMA practitioners of traditional systems will declare that the majority of their learning happens during unscheduled, informal gatherings rather than within the confines of the set schedules in the training hall.

Social structure, hierarchy and relational imperatives

Many FMA systems today practice a hierarchical system adopted from other martial arts. This involves the issuance of ranks through a belt system, a certificate-based recognition of skills and various modes of showing respect. There are, however, still some groups who practice and teach the art the way they were taught by those whom practitioners refer to as “first generation masters.” These are individuals who started to openly teach their respective arts. Many of them were born in the late 19th to early 20th century.

The social structure in groups who hold on to this tradition is informal in nature. By that we mean, the structure and relationships were not codified but rather relied heavily on Filipino cultural values and imperatives. Hierarchy was classified into two categories: the Instructors (usually subdivided into Master and Instructors, referred to by the following titles of Guro and Punong Guro/Maestro) and students. While many call their founding Masters by the term “Maestro” or the later title of “Grandmaster”, in reality, many informally refer to them by traditional titles given to individuals who have earned the respect of others through a combination of age and wisdom gained through experience. This includes the prefixes “Mang” and “Manong” as well as the term “Tatang” or “Tatay.”

Under these traditional structures, “senior students” may or may not exist. Unlike other martial arts traditions which practice a rigid adherence to overtly recognizable symbols of rank and protocol, these delineations are not as obvious within the context of traditional FMA training. There are no uniforms nor rank indicators worn by the practitioner. In many cases, overt respect such as that of “bowing” is only accorded to the teacher and even then, some teachers choose to dispense with this requirement altogether.

In the absence of rank certificates, FMA masters were primarily recognized by their reputations which were gained through their actions and clear display of skills. As FMA master Pedro Reyes pointed out, each master is “sui generis” (unique), in that genealogy or certificates are not as important. Students choose to study under a teacher based on that teacher’s demonstrable abilities (Reyes 2001, 131-132). This is reflective of how Filipinos view authority and power.

In pre-Hispanic Filipino society, there was no word for “primary Datu” (primary chieftain). There were, however, those referred to as “pangulo” (head or leader). These were individuals who were recognized as “primus inter pares” (first among equals). While lineage did play a minor role in a Datu’s authority, their power stemmed from personal characteristics and capacities based on qualities our forefathers considered to be of value, rather than the genealogy or lineage itself (Scott 1994, 128-129; Aguilar1998, 55-56; Angeles 2007, 10-11).

Traditional FMA teachers are likewise choosy with regard to students they take in, especially those who come from the first generation. For a student to be accepted by the maestro, he must pass standards set by the master. There is a clear and distinct “pamantayan”. Pamantayan comes from the root word “pantay” which is roughly translated to “equal” or “at the same level.” Pamantayan is not merely based on outside impression. At the core of making a value judgment lies the concept of “diwa”. Diwa represents the spiritual core of the value system; the sum total of collective sentiments and psyche of a people. It is the wellspring from which “asal” (behavior; expressive core) and the corresponding “halaga” (extrinsic worth) arise (Jocano 1997, 27-29, 54-60). These pre-requisites may differ from teacher to teacher. Some students tell of stories where it took them months in what is akin to a courtship process, before they were let in (Gonzalez 2015, 62-63; Wiley 1994, 26; 1996, 257). Some require referrals from trusted individuals whom the teacher knows personally while others, such as the late master Regino Ilustrisimo relied on an esoteric form of ascertaining an individual’s worthiness for acceptance (Inosanto 1980, 23-24).

In Filipino Martial Arts, as in Filipino Culture, the concept of loob plays an important role in coming up with value judgments. “Loob” (literally translated as “inside” or “interior”) is an integral part of how Filipinos view others. Despite this translation, however, within the context of Filipino usage, it is so much more than mere physical space. It involves elements of consciousness, feelings and inner strength (Alejo 2018, 29). Filipinos often refer to loob when speaking of either the self or of others. Good feelings are recognized as “magaan ang loob”, feeling bad is known as “masama ang loob” while estrangement is described as “malayo ang loob.” It can be safe to say that Filipinos understand and can be understood in terms of their interiority or “kalooban” (Jocano 1997, 95-96).

Kapwa

While teachers initially gain respect through demonstrable skill, this is however insufficient as a basis for a long-term relationship. Teachers and, by extension, other members of their group, must likewise demonstrate relational imperatives perceived to be culturally important. These relational imperatives are expressed in sets of inter-relational triads of cultural values. First and central of these triads is the concept of “kapwa.” Kapwa is defined by the late F. Landa Jocano as follows:

“This term refers to the perceived state of ‘being part of’ or being on equal terms with others as in being members of the same organization, peer group, nationality, or race.”

Kapwa refers to the shared identity and “pakikipag-kapwa” (being one with others) serves to demonstrate this unity with other selves” (Jocano 1997, 61-64; 1999, 66).

Kapwa also embodies our emphasis on equality of status as part of a social collectivity regardless of the position or rank we hold in the collective. It encapsulates the principle of egalitarianism (physically embodied in the non-emphasis on rank in traditional FMA practice) and therefore addresses the common expectations for fair and equal treatment. This makes kapwa a source of ethical behavior. (Jocano 1997, 63-64)

While this description refers specifically to human organizations, it is important to note that this term is used for non-human relationships as well. This can be glimpsed in Filipino terminology. Kapwa is often used to describe an affinity with other broader categorical groups as well such as kapwa-nilalang (fellow creature) and kapwa-hayop (fellow animal). This demonstrates a recognition of a shared essence which binds individuals to the others and shows how the concept of interiority (loob) is expressed in worldview, culture, and consequently, in language. Kapwa gives us the tools by which we define who we are based on our relationships with others. The concept of kapwa likewise highlights the importance Filipinos give towards interdependence and harmony in our relationships within the systems we interact in (Jocano 1997, 63-64). Kapwa is composed of three normative behaviors: pakikitungo, pakikisama and pakikiramay ( Jocano 1997, 65; 1999,66; Jocano, Jr. 2013, 5).

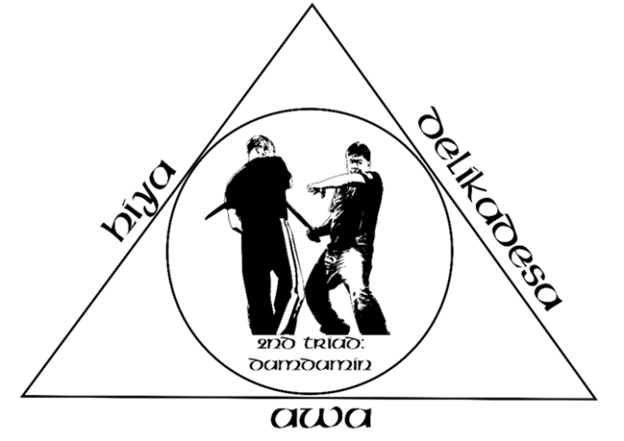

Figure 2. Image based on the article “The Filipino Way” by Felipe Jocano, Jr. (FMA Informative 91, 2013)

Pakikitungo

Pakikitungo refers to the ability to adapt to situations beyond one’s control. It commands people “to adjust, to act humbly, to relate with other people properly, to deal with people in the most appropriate way, and to maintain grace under pressure” (Jocano 1997, 67; 1999, 67).

Given that FMA practice is heavily reliant on inter-active partner drills, an individual’s skills development heavily relies on both parties adhering to shared goals and harmonious interaction between them. In FMA circles, the ability to “flow” is commonly used to describe one’s command of pakikitungo (Jocano, Jr. 2013, 7-8). Within this context, partners cannot be selfish. They have to learn to constantly adjust to their partner’s movements, giving way when necessary, reading intention with the goal of maintaining the flowing exchange of the drill and ensuring that both sides have room to learn and improve (Jocano Jr. 2013, 7-8).

Senior students who have already developed superior skills are expected to adjust to those less senior than themselves, ensuring that they do not make it too difficult so as to smother the junior, nor too easy so that they do not learn anything new. They are expected to have discernment in “pagtimpla” (roughly translated “how to mix”) and “diskarte” (acting appropriately based on this discernment). This interaction covers aspects of relation (practitioners need to ascertain their partners and then decide the terms by which they will relate), humility (senior practitioners need to control themselves and give their juniors space to be able to flow with them in the drill) and adjustment (drill partners need to learn to adjust appropriately within the context of their partners abilities and movement). All these are physical and psychological expressions of pakikitungo within the context of FMA partner drills.

Pakikisama

Pakikisama, derived from the root word “sama” (to accompany) functionally refers to being “concerned about, supportive and helpful at all times. It defines the inter-personal level of relationships, also serving as a technique for nurturing good public relations (Jocano 1999, 66).

On a personal level, pakikisama involves the subordination of one’s own pride and ego. It involves accommodating others to show concern for and support of another individual’s well-being. Thus, pakikisama involves a high level of both self-awareness as well as self-control (Jocano Jr. 2013, 6). FMA practice is a hazardous affair given that it deals with weapons. As such, safety is a constant issue. Pakikisama provides the cultural pressure to maintain self-control within such an environment. As skills are developed, individuals become prone to issues of pride and ego. Those who fall for this tend to show off, often at the expense of less-skilled individuals. These individuals who are deemed as “hindi marunong makisama” (does not go well with others) are not only dealt with by the instructor through punitive action such as suspension or in extreme cases, even expulsion, but likewise face pressure from the collective due to the culturally negative undertones a lack of pakikisama connotes.

Pakikiramay

Pakikiramay is derived from the concept of “damay” and connotes involvement or sympathy in the fortunes or misfortunes of another individual. Another translation for this would be crisis-oriented compassion (Jocano 1997,68 ; Jocano Jr. 2013, 8-9). Within the context of FMA practice, this expresses itself in empathy for other individuals. Through pakikiramay, members of traditional FMA groups either console or encourage each other. Many traditional groups practice a socialized tuition scheme to accommodate others who cannot pay their dues as an expression of pakikiramay. This form of active compassion more often than not extends beyond the training hours and well into the personal lives of group members as well. Despite all these examples, it is on a larger context however where pakikiramay shows its purest expression.

FMA practice traditionally has its roots in the defense of the community. Practitioners honed their fighting abilities with the thought that one day, this may be put to good use to protect others (Macachor/Nepangue 2007, 69-77). This is where pakikiramay is seen expressed in its truest form. Fueled by compassion for their “kapwa,” these individuals show themselves willing to put their lives on the line, facing the possibility of death itself, in defense of those who cannot defend themselves.

Damdamin

The second triad of Filipino cultural values deals with the emotional aspect of relational imperatives. This is collectively termed as “damdamin” translated as “feelings.”

Damadamin acts as the guiding criterion by which most Filipinos interpret and comprehend events, situations, conditions, relationships and activities, either consciously or unconsciously. Filipinos are emotional by nature. While we are still rational in our decisions, this more often than not, involves a deep emotional base (Jocano 1997, 70-72). As a cultural imperative, Filipinos find value in maintaining harmony. This creates a sensitivity to feelings and corresponding cultural elements designed to ensure that harmony is maintained by not hurting “damdamin.” These are the following: delicadeza, awa and hiya (Jocano 1997, 72; 1999, 68).

Figure 3. Image based on the article “The Filipino Way” by Felipe Jocano, Jr. (FMA Informative 91, 2013)

Delikadesa

Delikadesa involves our sense of propriety. A direct translation for this is “being proper”; a refinement of behavior or propriety (Jocano 1997, 77). Given this definition, delikadesa can roughly be translated as “knowing one’s place”. To know one’s place is to position oneself appropriately given the physical, emotional or psychological state of things. In conflict-of-interest situations, for example, a person with delikadesa will step away without being told knowing that this is the appropriate thing to do. The range and limits of relationships between individuals are defined in the context of “space”. Thus, one can be intimate, near or distant from a person (Jocano 2001, 23-24).

Martial arts training in general is governed by the control of space. This is much more emphasized in weapons-centric arts as the tip of a weapon travels at much faster speeds than a punch or a kick. Due to this, control of space and knowing where to place oneself appropriately in relation to the opponent and his weapon becomes paramount. In Filipino Martial Arts, the use and control of space is heavily emphasized and is usually referred to as “sukat” or “kwenta” (to measure).

Space in FMA is determined by several factors. These factors are the range; the distances for weapons to be employed effectively, and angle; the position in relation to the opponent. The action a practitioner takes with respect to these two factors; the practitioner’s choice of range and angle (also referred to as “zoning”) is dependent on the intent or what he wants to do. Lessons and inter-active drills serve as templates through which practitioners are able to explore positional possibilities based on intention and execute their planned responses. When a particular position is deemed inappropriate, it is termed “delikado” (dangerous).

Inter-personal relationships can also be likened to “space.” Filipinos often refer to the depth of relationships in terms of space via phrases such as “malayo sa loob” meaning “far from the heart.” In a highly informal environment, individuals are still expected to know their place within the group or how to relate to others through delikadesa. This can only be done by being observant of the emotional state and body language of others. This sensitivity to the internal state of others translates into the fighting arena as well. By harnessing this sensitivity, a practitioner can use his knowledge of the emotional state of his opponent to his advantage (Jocano Jr. 2013, 12-14).

Many of the first generation masters harnessed this sensitivity to a high degree. An example of this is the late Master Antonio “Tatang” Ilustrisimo, the founder of an FMA system called “Kalis Ilustrisimo.” Many have described his strategy as “situational combat” or “praksion” defined as “striking a fraction of a beat faster”; a strategy of striking pre-emptively at the very moment an opponent makes the decision to strike (Wiley 1996, 208). “Tatang” (as FMA practitioners fondly called him) had fine-tuned this sensitivity to the point where he could strike his partner at will. The thing is, while praksion is defined as striking a half-beat faster, his strikes were not necessarily extremely fast. The timing of his strikes, made possible by his sensitivity to physical and emotional space are what made it seem that way.

Hiya

Hiya, defined interchangeably as shame, shyness, timidity or embarrassment is another emotionally charged Filipino cultural aspect which is often interpreted as a value rather than a norm. It is still related to the need to maintain harmony and preserve feelings. It is a social norm which guides politeness, good manners and right conduct, especially in public places (Jocano 1997, 73-74; 1999 68).

In essence, hiya has to do with saving face. Like all the other cultural imperatives, it works together with other concepts in governing the actions of a person within a group. Within the context of FMA practice, hiya is strongly linked to the concept of dangal (defined as “honor”, which will be tackled later in this chapter).

Within a martial arts framework, the primary metric or pamantayan for quality is the actual fighting ability of an individual. Being an art which involves hand-to-hand combat, this is understandable. Hiya serves to ensure that groups in general, and instructors in particular, maintain a high level of quality in their training, preserving the combat applicability of the art they practice and teach. Remarks such as “mapapahiya tayo diyan” serves to ensure members of that particular FMA community live up to the standards and reputation of the group. This prompts all members of the group to act and ensure that these standards are indeed met since hiya not only applies to the instructor but to the whole group as well. The dangal of the group is at stake and the group will stand to lose face, in which case it will be “Nakakahiya.” Because of this, the group collectively works hand-in-hand to ensure that quality is preserved.

Hiya, when interacting with such imperatives as delikadesa, pakikiramay and pakikitungo likewise ensure a certain mode of behavior within the group. When fighting prowess is the metric, there is a tendency for the ego to take over often at the expense of the less skilled. When interacting with pakikiramay, which involves empathy and compassion, individuals are encouraged to control this urge. They thus refrain from embarrassing others (pahiyain) knowing that they themselves do not like being embarrassed (mapahiya).

Awa

Awa is closely related to pakikiramay in that it involves compassion, mercy, charitableness, kindheartedness and sincerity (Jocano 1997, 79). A direct translation of awa is “pity.” Martial Arts in general, involves the physical imposition of one’s will over another within the context of mortal combat (Jocano Jr. 2013, 14-15). Suffice it to say that martial arts is inherently violent in nature. This is all the more true when the fighting involves weapons of any kind. Filipino Martial Arts teaches techniques designed to quickly end an altercation in the fastest and most efficient manner. Highly skilled individuals with this knowledge are dangerous. They are imbued with power and strength. What stops them now from going overboard? This is where awa steps into play. As a cultural emotional imperative, FMA instructors not only instruct students on the ruthlessness of mortal combat. They also emphasize the importance of “balance.”

Filipinos see the world through binary eyes, usually described in terms of hot or cold. A state of harmony or equilibrium involves a balance between these two binary forces. Thus, in our eyes, unfavorable conditions are the result of disequilibrium or an imbalance within the system, while a state of balance causes favorable conditions (Jocano 2001, 27). The cultural imperative of awa serves to balance the inner state of FMA practitioners where the strength and power which comes with knowledge and skill must be balanced with mercy and compassion. Power is never pursued for its own sake (Jocano Jr. 2013, 14-15).

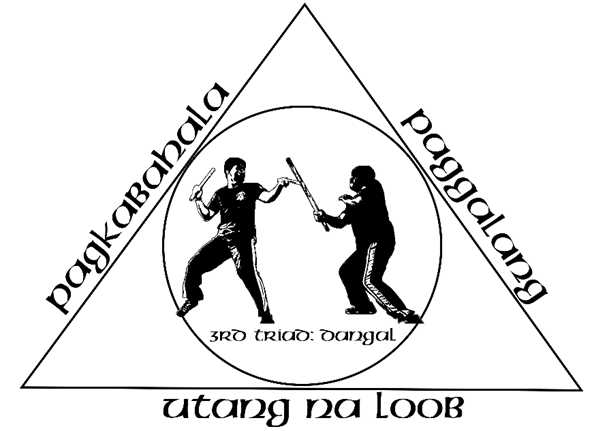

Dangal

Dangal is directly translated as honor and dignity. In Filipino cultural usage, this refers to the moral and ethical aspects of Filipino social interaction (Jocano 1997, 80; 1999, 70). Dangal is not necessarily founded on particular religious doctrine however, but is rather a social construct (Jocano Jr. 2013, 16-17). Dangal integrates kapwa and damdamin and expresses itself into a moral and ethical mode of interacting with others through determination of “What is right?” — introspection, “What demonstrates care about others in the context of commonly accepted moral principles such as honesty, fairness and self-discipline?”– contextual analysis and culminating in “Are my actions morally right?” – the decision to act (Jocano 1997, 80). The dominant supporting norms for dangal involve the following: pagkabahala, paggalang and utang-na-loob.

Figure 4. Image based on the article “The Filipino Way” by Felipe Jocano, Jr. (FMA Informative 91, 2013)

Pagkabahala

The root word for pagkabahala is “bahala” which involves “taking charge or taking responsibility.” While this is used for virtually anything, it is often also used in the context of other individuals (Jocano 1997, 81). When one says, “Ako na ang bahala nito” (I am in charge of this) that person is pronouncing that he or she is taking responsibility and accountability for whatever “nito” means, be it a thing, a place, an event, a task or a person. Through pagkabahala, individuals express their concern for the whole as demonstrated through action, elevating it from an ordinary social base to a moral plane. Concern and care for others is expressed not just through personal interaction, but likewise through the consistent and conscientious dispensing of one’s role within the group (Jocano 1997, 81-82).

Pagkabahala is both taking leadership and being empowered for a leadership role. When interacting within the context of dangal, for example, individuals are morally obligated to look after the welfare of their fellow practitioner’s development. Those who know more share what they know and help develop the skills of those less skilled. They take the responsibility for ensuring dangal is protected by providing support for their Maestro by helping teach the newer members of the group with or without an organizational hierarchy which directs them to do so. They do this because it is understood that dangal is each and everyone’s responsibility. In cases where the instructor specifically says to a practitioner “ikaw na bahala” he is likewise empowering that individual by bequeathing authority, thus elevating that person to a leadership role (Jocano Jr. 2013, 17-18).

Pagkabahala is an integral part of who we are as a people. In the old days, members of the community skilled in martial arts deemed it their responsibility to protect the community from outside forces which may pose a threat. They were not full-time soldiers. These were ordinary folk who took this responsibility upon themselves voluntarily. We can still see this cultural imperative in action when see the Barangay-Tanod system today.

Paggalang

Paggalang or respect is one of the first things martial artists are acquainted with regardless of system, style, or country of origin. As a matter of fact, the overt action of showing respect is the very first lesson for generations of martial artists all over the world. There are two forms to “galang” (the root word of paggalang): internal and external. External respect refers to that which is bestowed on a person on account of that person’s status or position in society. This is most evident in institutional settings where respect is shown to a person by virtue of the office that person holds. Internal respect, on the other hand, involves the pamatayan of a person’s diwa. It is based on how that person is viewed by the community in terms of attributes that particular community values. It is based on character. Galang is also outward and inward. Inward respect or self-respect demands that a person holds himself accountable to a certain standard of personal integrity. The outward aspect deals with how individuals interact within the environment they interact in. This is expressed both vertically and horizontally, to superiors, peers, and subordinates (Jocano Jr. 2013, 18-19).

In traditional FMA groups, the outward expression of galang may vary. Some are very strict on certain modes of conduct while for others, it can be as subtle as doing a “Mano po” whereby someone raises the hand of an elder to one’s forehead. Traditional FMA systems which do not rely on ranks or certificates, external or institutional authority, de-emphasize the protocols associated with respect. Respect is not specifically demanded but rather earned through the demonstration of skills and character. This is due to the fact that in the absence of external expressions of status, individuals are forced to look beyond the superficial.

Utang-na-loob

Utang-na-loob (translated as “debt-of-gratitude”) is one of the most misunderstood of Filipino cultural norms. This is understandable given how this has been abused time and again for personal interest and gain. As a matter of fact, western students of Filipino Psychology surmise that this is one aspect of our culture we can do without and even strive to eliminate (Jocano 1999, 71). Regardless of how utang-na-loob is used, it remains an indispensable part of our cultural identity and society. As a moral rule and obligation, utang-na-loob demands that we reciprocate goodwill with goodwill and underlies the importance of this reciprocity to social unity and harmony. It strengthens group solidarity by providing a social contract amongst its members (Jocano 1997, 83). It demands that an act of goodwill must be balanced by the same.

The observance of utang-na-loob is strongest in the traditional and less organized FMA groups. In these groups, teacher’s fees are not even fixed. Many operate on a socialized scheme for sustaining the group’s needs while ensuring that even those who have less resources to share are able to gain access to the same quality of instruction. It is through this cultural norm that a teachers needs for example are met by students as a sign of repaying their utang-na-loob despite the absence of fixed fees, reciprocating the sacrifices the teacher has made in instructing them.

Conclusions:

Cultural heritage as expressions of worldview

Cultural elements are physical expressions of how a people view the world, their place in it and how they must relate to it. The Martial Arts is no different. Traditional Filipino Martial Arts (Arnis-Escrima-Kali) act as both repository as well as vector though which Filipino culture is both preserved and propagated. This can be seen in traditional group organizations, the relational imperatives between its members, and physically in how the material is presented, taught and applied.

This expression can be summarized into two main points:

- Seeing everything as being part of a larger system where individual elements interact with each other and are united by a common core or essence.

This can be seen in the way FMA practitioners see the art as a whole. The various weapons taught are united by a core set of principles and strategies. These principles unify the whole into a congruent, consistent and non-self-contradicting system. For practitioners to realize their goal, that of acquiring skills needed to survive and be victorious in mortal combat, they must be able to internalize how individual elements relate to each other and gain the ability to seamlessly flow between these elements. Experienced teachers recognize the value of individual components, using a particular component to strengthen the student’s understanding of other components within the system. They recognize this inter-relatedness as essential to student development.

Espada y daga (sword and dagger) for example is best understood in relation to double-stick utilization. The various drills employed by specific systems relate to each other in the same way. They serve to highlight the advantages and disadvantages of the various ranges, angular positions and techniques when viewed against the other drills. In the advanced level of practice, practitioners gain the ability to flow from one drill format to another smoothly. The same can be said to be true for how individuals view themselves within the context of their martial arts groups as well. They recognize the inter-dependent nature of their relationships within the group and see themselves not just as individuals, but as part of a larger society.

- For the system to be stable, balance and harmony must be maintained.

For a particular FMA system to be effective, it must maintain integrity. This means protecting its internal consistency by ensuring that superficial elements such as specific techniques and movements are consistent with the core principles and strategies of the system. When outside influences (such as techniques learned from other martial arts traditions, observed in others or a specific movement or technique a practitioner has visualized) are considered for synthesis, these are weighed against the core principles and strategies. Anything which does not align with these are promptly discarded as this will interfere with the balance and harmonious relationships of elements within the system. In effect, the essence must be the same for it to be of value to the system.

That can be said to be true of the relationships between individuals within the group as well. All these cultural norms strive to create harmonious relationships characterized by balance and reciprocity. Extraordinary strides are taken to maintain equilibrium and a sensitivity to anything which may disrupt this, is developed to a deeper degree when compared to other cultures. Individuals recognize that their actions will have effects both seen and unseen. Being part of the system, these effects will eventually come back to affect them. The nature of how their actions will affect them in the future, whether favorably or unfavorably will be highly dependent on how sensitive they are to their surroundings and the corresponding actions they will take based on their interpretation of their surroundings.

Just like the various components of the art itself, the various cultural norms do not stand alone. They serve in a complex, inter-related web. Through this, a balance is achieved. By aligning oneself to all these standards which act supportively of each other, one is driven to uphold community ideals. It is in imbalance that the negative side of these various cultural norms come out; when such concepts as utang-na-loob and pakikisama are abused (Jocano 1997, 83-84).

Cultural appropriation

As previously mentioned, the idea of “organization” similar to what we see in other arts is relatively new to the FMA community. This involves commercial schools with specific training times and locations, hierarchical systems characterized by the use of a belt system, a linear presentation of material and pedagogical method, and a skills recognition system where certificates become the primary consideration for competence. This evolution is practical in nature as this gives FMA schools the ability to compete with more organized martial arts systems such as Tae Kwon Do, Judo or Karate-do, thus making it a financially viable endeavor for the instructor. There are, however, problems with adopting this lock-stock-and-barrel as this does not take into consideration the underlying cultural base which gave rise to the Filipino Martial Arts in the first place. While the resultant combat effectiveness of traditional teaching vis-à-vis the newer “commercialized” organizational systems is still debatable and requires further study, we cannot deny that the cultural context which has been essential to teaching the various FMA systems in its fullness is, at the very least, watered down.

Cultural elements hold specific meaning for the people to whom they belong. It is this underlying meaning which dictates its relevance. The underlying relevance is not confined to ideas, symbolism or religious/spiritual beliefs alone. In the case of FMA, the cultural undertones have a direct effect on the practitioner’s ability to fully understand, apply and impart this knowledge to others. It is instrumental in skills development. It is a complete system of mutually supporting elements which do not stand alone but rather interact with each other to define and create a wholeness. One cannot therefore merely appropriate specific elements without knowing the underlying cultural context.

A classic example of this has to do with FMA practitioners from other countries. Foreign practitioners often come to the Philippines with very specific ideas of skills they want to learn only to have difficulty grasping the core concepts of what they set out to learn. Thus, in the quest for a deeper understanding of the material before them, they inadvertently interpret these within the context of their own culture and experience. Many foreign FMA practitioners likewise embrace other aspects of our culture out of the desire to be “more Filipino.” In one case for example, an American male wore a Muslim malong (tube skirt) while executing FMA techniques in a public demonstration in his home country. For one thing, Arnis-Escrima-Kali is not a Muslim martial art as the Muslims have their very own Silat and Kuntaw. On another, the malong was worn in a manner done by the women of the Muslim community.

As a people, we have to define what our cultural heritage means to us and clearly communicate this meaning at every opportunity. When cultural elements are transposed to another culture, it is inevitable that the adopting culture will implant its own identity and cultural context upon it, eventually claiming ownership of that element. This is unless, of course, the original underlying meaning and relevance is strongly communicated and preserved. By ignoring this, we can lose ownership of our very own cultural heritage. We do not want to go the way of Japanese Jujitsu for example, where the term is nowadays more strongly associated with the Brazilians rather than the Japanese.

Culture and the peace process

Cultural Heritage, even something combative in nature such as Filipino Martial Arts can be harnessed as a tool in the peace process. FMA emphasizes the inter-relatedness and the need for achieving balance and harmony within a system. This is achieved by looking beyond the superficial, into the core which binds the individual components together into a harmonious whole. The same emphasis and focus on the commonalities and shared essence of Mindanao’s tri-people (Christians, Muslims, Lumad/Indigenous tribes) for example, can be used as a tool in the same way FMA teachers use the common core to bring harmony and congruence to the systems they teach. This is achieved using the very same techniques FMA teachers have been using for generations wherein the new is introduced in the context of the familiar; social harmony is emphasized within the context of harmony within FMA systems.

Likewise, in traditional FMA groups, the relational imperatives are reinforced in a positive way regardless of political affiliation or belief system. Many FMA groups are composed of a very diverse membership base who subscribe to very different worldviews. Yet they co-exist within the system, helping each other in their shared goal of learning as they subscribe to the shared Filipino cultural imperatives of the group.

Cross-disciplinary applications

The academe is another area where the Filipino view of inter-relatedness can be harnessed. When viewed through this lens, students of the social sciences will be able to understand the complex relationships between the various fields in the social sciences and their individual effects on the whole. Through history and anthropology, we get see who we are and why we are who we are. Sociology and Political Science describe how this identity manifests itself within the context of our society. A thorough understanding of the complex forces that shape our present as individuals and as a collective aids us in grasping the challenges we experience in the present. This is essential if we are to come up with solutions that ensure a better future.

The late management guru, Peter Drucker is credited with the saying, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” Culture is indeed a buzz word in management circles today. It is seen as the biggest factor in ensuring a company’s long-term success and sustainability; something of immense strategic value. Filipino culture, when seen from a management perspective, has a lot to offer in the world of corporate management. Management professionals and educators no longer view organizations as machines but rather as living ecosystems involving complex symbiotic and interdependent relationships between components. Buzz words such as “buy-in” and “employee engagement” are making the rounds in leadership and management material in the context of this change in organizational view. Corporate policies are viewed in light of short, medium, and long-term effects, both direct and indirect. Employee engagement, fueled by buy-in and ownership, is measured in recognition of the fact that this has an effect on over-all productivity. Collaboration teams are put in place to facilitate smooth interface between departments and partners. In today’s workplace, companies value skills such as systems thinking, collaboration and sensitivity essential to dealing with diverse individuals and organizations who are, in many cases, located halfway around the world.

While managers strive to acquire these skills, these capacities are inherent in Filipinos because of our culture and worldview. It is in our cultural DNA. A good case in point would be the Filipino penchant for consultation and consensus-building as a leadership style, given the value Filipino culture places on relationships and harmony (Jocano 1999, 92-93). While this was once viewed negatively as a waste of time through western eyes, it is highly encouraged these days and seen as essential if one is to ensure buy-in and ownership from others in the team. This is but one example of many, but it serves to illustrate just how Filipino culture has the potential to be a template for management in the 21st century.

In many ways, our cultural heritage serves as a mirror informing us of who we were in the past and who we are in the present. This does not stop here, however. Our culture, encapsulated and preserved through diverse expressions, can l help us be who we want to be in the future.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This is part of the book ” Transfiguring Mindanao” published by the Ateneo de Manila University which is meant to be a primer on Mindanao covering historical, political, ecological, economic and cultural facets.

This is the original chapter prior to the official editorial review for the book but has been proof-read by Prof. Felipe Jocano, Jr. of the Anthropology Department of University of the Philippines – Diliman and Dr. Jose Jowel Canuday, head of the Sociology and Anthropology Department of the Ateneo de Manila University.

REFERENCES

Aguilar Jr., Filomeno V.1998. Clash of Spirits: The History of Power and Sugar Planter Hegemony on a Visayan Island. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Alejo, Albert E. S.J. 2018. “Loob as Relational Interiority: A Contribution to the Philosophy of the Human Person.” Social Transformations 6, no. 1 (2018): 29-53.

Angeles, Jose Amiel. 2007. “The Battle of Mactan and the Indigenous Discourse on War.” Philippine Studies 55, no. 1 (2007): 3-52.

Canete, Dionisio A. 1993. Eskrima Kali Arnis. Philippines: Doce Pares Publishing House.

Gonzales, Rey Carlo T. 2015. “Filipino Martial Arts and the Construction of Filipino National Identity.” PhD thesis, University of Manchester, 2015. https://www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/files/54566917/FULL_TEXT.PDF

Inosanto, Dan. 1980. The Filipino Martial Arts as taught by Dan Inosanto. Los Angeles, California: Know Now Publishing Company.

Jocano, F. Landa. 1997. Filipino Value System. Quezon City: PUNLAD Research House.

_____________.1999. Working with Filipinos: A Cross-Cultural Encounter. Quezon City: PUNLAD Research House.

_____________.2001. Filipino Worldview: Ethnography of Local Knowledge. Quezon City: PUNLAD Research House.

_____________.2003. Folk Medicine in a Philippine Municipality. Quezon City: PUNLAD Research House.

Jocano, Felipe Jr. 2001. “A Question of Origins”. In Arnis: Reflections on the History and Development of the Filipino Martial Arts, 3-8. Boston, Massachusetts: Tuttle Publishing.

_____________. 2013. The Filipino Way. FMA Informative, 91. https://www.fmainformative.info/Informative_Issues/2013/FMA_Informative-Issue91.pdf

Macachor, Celestino C. and Napangue, Ned R. M.D. Cebuano Eskrima: Beyond the Myth. Xlibris Corporation, 2007.

Nepangue, Ned R. M.D. “Questioning the Origins of Eskrima” In Arnis: Reflections on the History and Development of the Filipino Martial Arts, 9-14. Boston, Massachusetts: Tuttle Publishing.

Scott, William Henry. 1994. Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Wiley, Mark V.1994. Filipino Martial Arts: Cabales Serrada Escrima. Singapore: Charles E. Tuttle Publishing.

_____________1996. Filipino Martial Culture. Singapore: Charles E. Tuttle Publishing

Yambao, Placido. 1957.Mga Karunungan sa Larong Arnis. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.